The Lucinda Honstain quilt in the collection of the International Quilt Study Collection and Museum is being shown at the American Folk Art Museum in Lincoln Square in Manhattan. Made in New York City: The Business of Folk Art is up until the end of July. Museum curator (and AQSG member) Elizabeth V. Warren has written a catalog, available from the Museum Store.

I was pleased to see the thread that runs through the exhibit. When I began this blog a year and a half ago I commenced with a rant about all the "quilt history" we have to unlearn.

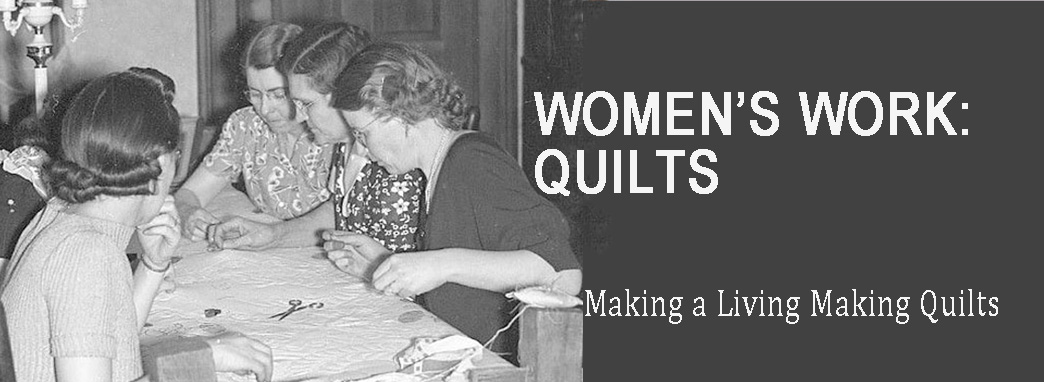

One woman: one quilt ---from pattern idea through ragbag to binding---with a little neighborly assistance in the quilting. Money was never mentioned (you didn't need money if you were thrifty enough, apparently.) No one ever shopped in a city store, sold a pattern, bought a bundle of scraps, hired someone to mark her quilt top, made up fabric kits or taught patchwork in a needlework class. Women did not work for pay, and they certainly didn't create time-honored American crafts for money.

The irony here is that Webster, McElwain, Finley, McKim and Nancy Cabot each made a living doing many of those activities....

Quilting demonstration at a Florida folk art festival

Every one of those authors painted a false picture of the past by ignoring the economic and commercial aspects of women's needlework at which she herself was succeeding admirably. Plus: I wanna know: Did city dwellers ever make quilts?"

Warren has answered my last question.

Elizabeth V. Warren

and a New York quilt

"The exhibition is divided into two parts. 'The Art of Business' includes paintings, quilts, sculpture, and signs that either depict or relate to businesses that operated in the five boroughs of New York during this time period.

H. Prouse Cooper's Downtown Store

'The Business of Art' encompasses works that were the products of businesses that were producing what we today call folk art: pottery, portraiture, show figures, carousel animals, weathervanes, and furniture....

Commercial sign

"Despite the popular belief that folk art was a rural genre, it has flourished in New York City since the eighteenth century. Many pieces associated with the heartland and considered among the core expressions of American folk art were in fact manufactured and used in New York City."

"W. B. Dry Goods"

pictured in the Honstain quilt

Made in New York City: The Business of Folk Art: Up until July 28, 2019

http://www.artfixdaily.com/artwire/release/2751-made-in-new-york-city-the-business-of-folk-art