Stuffed work quilting, mid-19th century

Wholecloth quilt, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wool on one side, cotton on the other.

Marking the quilting design is particularly important in wholecloth quilts in which the quilting is the major decorative technique. These quilts are marked with the all-over designs before they are basted and put in the quilt frame.

Esther Wheat's wholecloth quilt in the collection of the

Smithsonian Institution

Wholecloth quilt 1790-1810, New England,

Collection of the International Quilt Study Center & Museum

#2006-007-0001

The quilting designs are difficult to photograph.

Linda Baumgarten's drawing of quilt

#2006-007-0001

But Linda Baumgarten has been drawing the patterns in wholecloth quilts using a computer-assisted-drawing program, revealing the complexity of the designs.

Quilt marking was also a drawing skill. And as we shall see in this blog every part of quiltmaking had a commercial value.

In 1822 Sarah Snell "Went to Mrs. Briggses to draw a feather on a bed quilt."

She may have drawn feathers as a favor or in trade but it is also

possible she was paid for her art.

Wholecloth wool quilt date inscribed 1833. One of the

latest of these popular New England style bedcovers that I have seen.

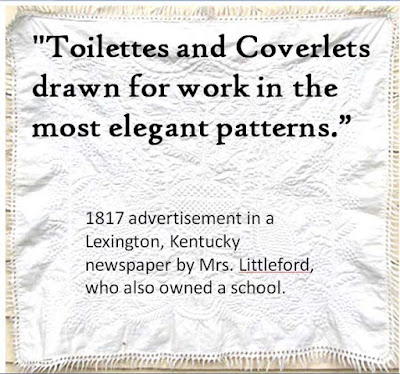

Mrs. Littleford would "draw for work in the most elegant patterns"

in Lexington in 1817. She'd mark a bed quilt (coverlet) or a toilette.

Early 19th century Toilette from Stella Rubins's shop

We might call a toilette a quilted dresser scarf.

These were quite the fashion in the first quarter of the 19th century.

Whitework bedquilts survive with dates throughout the 19th century

(and into our own times).

Wholecloth white cotton quilt date-inscribed 1849 by Elspeth Duigan.

Collection of the Smithsonian Institution

americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_556177

Elspeth's quilt is charming but not what one might term skillfully drawn. She probably marked it herself or with the help of friends and they might have marked it in the frame as they quilted it.

Recent Mennonite whole-cloth quilt from Ephrata, Pennsylvania

Helena Peters Ewert (1881-1962) lived in Hillsboro, Kansas. With an ill husband she quilted about 100 wholecloth plain-colored quilts for diversion and for sale. She quilted by herself. "Since she was being paid she was obligated to provide a consistently fine piece of work." Stepdaughter Marie Ewers Regier (1899-1982) who was only about ten years younger than Helena was the quilt marker in the partnership.

Sara Farley described Marie's marking process. She made a homemade light table by opening her dining room table and putting a piece of glass where the table leaf would go. A lamp under the table provided the tracing light. "Working in her spare time, Marie could mark a full size quilt in two weeks."

Anna Calem was another woman in the Hillsboro partnership. She hemstitched the quilt edges before Maria Peters added a crocheted edge treatment, a finish usually done for crib quilts.

Mennonites were not the only quilt markers working well into the 20th century. We heard stories in northern Kansas of women who were well known in their quilting communities for their drawing skills. Whether they were well-paid is a different story.