Bet Rash and family, North Carolina

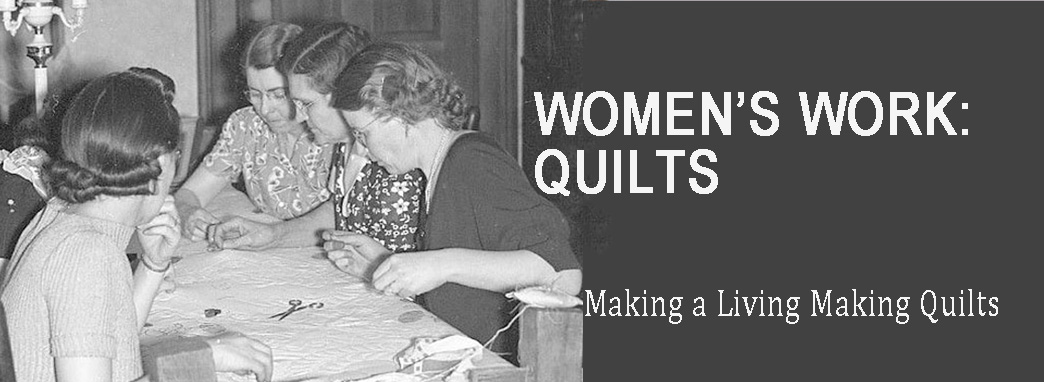

Women’s work and the Southern yeoman farmer’s story are two neglected areas of American history.

Jean Odom pointed out on our QuiltHistorySouth Facebook page a website at the University of North Carolina libraries---a great source of information about both.

Tobacco has always been a huge part of Southern farming and industry; in the early 20th century much loose tobacco was sold in small cotton pouches about 3 inches x 4, each tied with a short piece of string, a drawstring threaded through a gathered tube. At the end of the Great Depression in the late 1930s a billion bags a year were manufactured to hold loose tobacco. Three giant companies manufactured bags and sold them to the tobacco companies.

Susan Nelson has tobacco bags in her lap

By 1939 Durham, North Carolina’s Golden Belt Manufacturing Company had machinery to insert the strings but the other two relied on hand labor. It was women’s work and it had gone on for quite a while.

Reidsville, North Carolina’s Chase Bag and Richmond, Virginia’s Millhiser Bag Company used similar systems to put out the work, hiring a bag agent in communities to manage the work distribution, payment and return. Communities black and white relied on the at-home work to make ends barely meet.

Reidsville, North Carolina’s Chase Bag and Richmond, Virginia’s Millhiser Bag Company used similar systems to put out the work, hiring a bag agent in communities to manage the work distribution, payment and return. Communities black and white relied on the at-home work to make ends barely meet.

Jesse Lee Shepherd Family

Jesse Lee Shepherd was a young man who ran a small store in Reddis River, North Carolina. He farmed and worked about half time in a government program. With a wife and three children he added to his income as a bag agent, distributing work to be done through the store and trading store goods to the women workers when they returned the bags. Other agents paid in cash. Website records tell us how much the women earned.

Times were tough and the bag agents often had more requests for work than they could fill. The agent

in Leakesville, North Carolina figured there was a stringer in every household in his community. The work was tailored for women, repetitive hand work requiring dexterity (and good eyesight for close work) that could be done at home in intensive stretches, at social times, worked around housework and while caring for children. While it did not pay well, it paid and was often the difference between hunger and getting by in many households.

In 1939 bag stringing caught the attention of the National Labor Relations Board, concerned that no bag stringer was making the minimum wage. “Not long after the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, the Virginia-Carolina Service Corporation, based in Richmond, began lobbying for an amendment to the act that would exempt home workers. The Service Corporation commissioned a report to argue for the vital importance of the income earned from tobacco bag stringing by many families in Virginia and North Carolina. The authors of the report solicited and published testimony from agents who distributed the bags and from local government officials.”

Rather than feeling exploited, the women stringers protested losing their work. The website records economic information about each family and how the work benefited them. Dozens and dozens of families were interviewed and photographed inside and outside their homes.

Alice Dickman, Virginia

Times were tough and the bag agents often had more requests for work than they could fill. The agent

in Leakesville, North Carolina figured there was a stringer in every household in his community. The work was tailored for women, repetitive hand work requiring dexterity (and good eyesight for close work) that could be done at home in intensive stretches, at social times, worked around housework and while caring for children. While it did not pay well, it paid and was often the difference between hunger and getting by in many households.

The woman on the right cuts the yellow string.

In 1939 bag stringing caught the attention of the National Labor Relations Board, concerned that no bag stringer was making the minimum wage. “Not long after the Fair Labor Standards Act was passed, the Virginia-Carolina Service Corporation, based in Richmond, began lobbying for an amendment to the act that would exempt home workers. The Service Corporation commissioned a report to argue for the vital importance of the income earned from tobacco bag stringing by many families in Virginia and North Carolina. The authors of the report solicited and published testimony from agents who distributed the bags and from local government officials.”

Bessie Holsbrook's family holding bags

Mrs. Leacey Royall

Wall paper of magazine pages was decorative and somewhat insulating.

The photos are a remarkable record of the people of Virginia and North Carolina 80 years ago, their rural cabin homes, some new or well kept, others run down and rather miserable.

Go to the site and the list of workers towards the top on the right."The Workers."

Go to the site and the list of workers towards the top on the right."The Workers."

Choose any woman and get a little insight into our poorly understood history. Those who look to a

nostalgic rural past for a sweet view of a simpler life might use these short stories as a cautionary tale. Several are sad stories of true American poverty before universal public education, Social Security and Medicare. Such sophisticated items as a pair of reading glasses seem unobtainable.

Gertrude Maynard's Family

The women workers were dependent on husbands, unemployed, under-employed and in particularly tough situations, absent through death or divorce. Yet the short biographies are inspiring, telling us a lot about the universality of being female and how enjoyable repetitive handwork can be.

Mrs. Howard Kirkman

Here's our QuiltHistorySouth Facebook page: