"Quilt given to Rosa Benson Snoddy by her

mother & father when she married" in 1853,

Spartanburg, South Carolina

Laurel Horton has studied the quilts of the Snoddy/Black family and published a book and several online articles about Mary Black's inherited quilts. This one seems to be the oldest in the family collection.

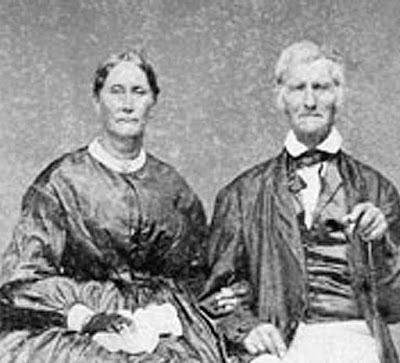

It's also the only one attributed to Mary Black's grandmother

Nancy Miller Benson (1809-1879) who lived her life in Spartanburg.

Spartanburg about the turn of the last century

Yardage, Collection of the Winterthur Museum,

which has several pieces. Curator Florence Montgomery

identified it as 1840-50, England. Curator Linda Eaton

describes it as 25-1/2" wide.

The fabric features a repeat of rose wreaths, circular panels

in two sizes and a rose sprig on the left and right.

The family was uncertain who made the quilt but the information passed with it indicated it was a wedding present for Rosa who married Samuel Snoddy.

"The Bensons could have purchased the chintz locally but it is quite possible that they demonstrated the importance of their eldest daughter's marriage by making a shopping excursion to Charleston to buy special items such as fabric for a wedding quilt.The information handed down by Mary Black is not specific about who made this chintz quilt; it is probable that Rosa's mother made it, alone or with help from family members or household slaves."The assumption here is that this was a gift especially for Rosa and that her parents gave it to her. Therefore, her mother must have made the quilt or supervised its making in their home, using fabric specially purchased for this quilt.

I am questioning that assumption. My main evidence is a nearly identical quilt in the collection of the Los Angeles Museum of Art.

Whole-Cloth Quilt, 1850, 97 x 97 1/2 inches.

Gift of Louise Bloom (M.90.144)

Both are quilted in a diagonal grid.

Rosa Benson Snoddy's quilt:

"She quilted the three layers in a simple, overall diagonal crosshatch. The chalk-like material she used to mark the quilting lines remains visible, an indication that the quilt has never been washed....The simple crosshatch quilting design could have been accomplished in a relatively short time, suggesting that Nancy Miller Benson chose not to take this as an opportunity to display fine handwork."

The major difference is in size with the LACMA quilt being a wider square with a full strip on the right here. Both have a length of about 6 wreaths. Rosa's quilt looks to be a redder colorway than the LACMA quilt, which is the greenish shade usually seen in this wreath panel. (Color difference may just be a color accuracy problem in the photos.) The LACMA quilt seems to have an added red binding while Rosa's quilt has the back brought over the front for an edging.

Single wreath in an album quilt dated 1843,

unknown source

My interpretation of this pair of quilts: They were made by professional quiltmakers in South Carolina about 1850. The Benson family bought the quilt readymade for Rosa's wedding.

It seems that someone stripped whole-cloth quilt tops of the wreath yardage and quilted them with a simple grid. How many others were made and sold?

When we hear the words wedding and quilt our conventional wisdom about quilts makes us assume a few things:

Wedding Quilt---Made by Mother

Two identical quilts---Mother made one for each child?

Two identical quilts---Mother made one for each child?

Why not Wedding Quilt---Bought by Mother?

I think it is time to think differently about women's work.

I think it is time to think differently about women's work.

See one of Laurel Horton's posts about the Black family quilts.