Women earning money by sewing were often viewed as miserable.

The wages were low (true) and the work was viewed as unpleasant (by whom?)

A large problem in studying the role of professional seamstresses in the making of fancywork like quilts is the 19th century aversion to discussing women's need to earn money. In the delusional view of an ideal society women were supported by men. Women needing to earn their own money were seen as disreputable failures.

"Decayed Gentlewoman" and family

One solution to the lack of employment choices for poor women was the Women's Exchange movement, which is generally thought to have begun in the U.S. in Philadelphia in 1833. The first annual report of the Philadelphia Ladies' Depository explains:

"In every large city, a numerous class of persons is found, whom the vicissitudes of fortune have reduced from a state of ease or affluence to the necessity of gaining a subsistence by their own personal exertions. The sufferings of females are, in most cases, greatly augmented by a natural feeling of delicacy, which leads them to shrink from observation...To devise means for relieving this class of females; to afford them facilities for disposing of useful and ornamental work in a convenient and private manner, a number of ladies consulted together, and as the most eligible plan for effecting the object, determined to open a small shop...."

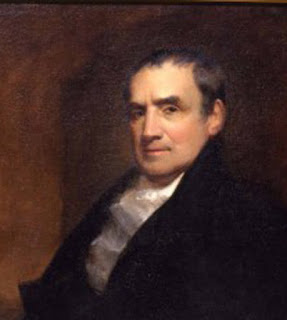

Mathew Carey (1760-1839)

Rather than helping the lower classes, these early charity organizations assisted women of "good families" who had fallen upon hard times. The idea was suggested by Irish-born Philadelphian Mathew Carey in 1828 who saw a need for discretion in paying these women better wages than could be earned at plain sewing for a wholesaler.

"There is no subject that has more painfully occupied my mind, than the very inadequate return, for I will not call it compensation, made to females who depend on their needles for support...I allude to persons who have been delicately brought up, but have all there prospects blasted, and who have not strength for any other employment than the needle…"

An 1855 sweatshop

Carey suggested that well-to-do "ladies form associations in order to have...poor women...taught fine needlework, mantua making [dressmaking], millinery, clean starching, quilting, etc. There is always great want of women in these branches." Elizabeth Phile Stott and her friends followed his suggestions and opened the Philadelphia Ladies' Depository.

Carey's idea caught on. The basic principles: Seamstresses were anonymous and items for sale handled discreetly. The shop sold fancy needlework of good quality made by women who received most of the price less a commission to support the agency. Plain sewing did not sell well and poorly made or unfashionable items were rejected, hopefully with advice or training in how to improve. Some agencies established sewing rooms for training and to provide pleasant working conditions. Charitably minded sponsors paid dues to the society and helped with the organization.

Organizations and shops were known by various names. In 1854 the Brooklyn Female Employment Society opened at 64 Court Street where women were given "a fair share of the work at fair prices, from the finest embroidery down to a Hickory shirt."

Sewing room at the House of Industry about 1900

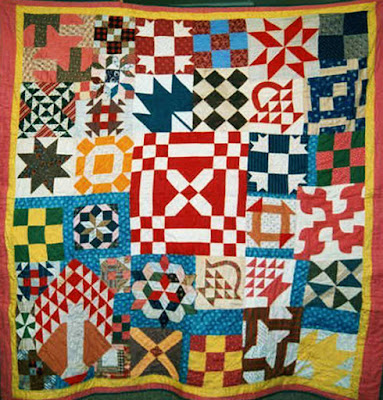

Quakers in Philadelphia developed a second agency, the House of Industry, to give work to a different class of women--- immigrants and poor women. Lucretia Coffin Mott, one of the founders, described a trip to the shop in 1879 where she paid $2 for two quilts, " very pretty red patchwork quilt and a red & mixed-calico not large." A 1919 directory described the work of the House of Industry as making "new quilts and recovering old ones."

Store at the Women's Educational & Industrial Union in Boston

https://www.facebook.com/greenwichexchange/

\

Follow this link to see an 1898 list of Women's Exchanges.

https://books.google.com/books?id=13riAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA332&lpg=PA332&dq=new+brunswick+jersey+ladies+depository&source=bl&ots=dy5qniK-bh&sig=3oYYFwlPjrYcIp3ynSnG1Nfej3k&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwifjpComaTbAhUDm1kKHY5hABgQ6AEINzAF#v=onepage&q=new%20brunswick%20jersey%20ladies%20depository&f=false

New York City's House of Industry advertised that they did quilting in 1843. A large size quilt was 15 something (maybe shillings?), a smaller one 9. They'd tack a comfortable for 3 or quilt one for 4.60.

The Brooklyn Women's Exchange is still open.