Priscilla Bell Wakefield (1751-1832)

Priscilla Wakefield was an English Quaker philanthropist from Tottenham, a member of the Barclay's banking family, who founded the Lying in Charity for Women, a maternity hospital for the poor in 1771. A few years later she began a School for Industry to teach girls academics and needlework skills. A practical woman and an excellent artist she realized a basic cause of women's poverty was the lack of acceptable female occupations.

In 1798 she published Reflections on the Present Condition of the Female Sex; with Suggestions for its Improvement.

Some of her suggestions:

"Designs for needle-work, and ornamental works of all kinds, are now mostly performed by men, and those who have a good taste, obtain a great deal of money by them; but surely this employment is one [that] should be appropriated to women."

See a post on Madame Lauzin's New York pattern shop here:

Radical in 1798, this idea seemed the status quo fifty years later in England and the U.S.

Wakefield also advised women with artistic talent to consider doing wood engraving for publications, miniature painting and scientific illustration, which she had done herself, writing and illustrating Reflections on Botany (1796) and other scientific books.

Another suggestion:

"Patterns for calico-printers and paper-stainers are lower departments of the same art, which might surely be allowed as sources of subsistence to one sex with equal propriety as to the other."

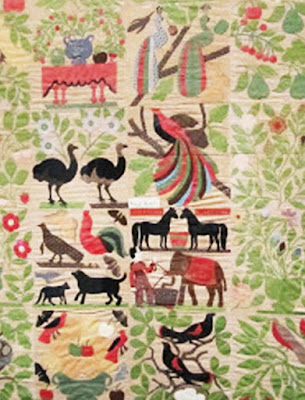

Detail of a painting, a design for a cotton print by

William Kilburn (1745-1818) About 1790

Victoria and Albert Museum

Paper-stainers must refer to wallpaper designs. Calico-printers is obvious. Whether it's a lower art?

British female textile workers at Burnley

They look to be wearing some kind of leather waist protectors.

Working as textile machine operators had been acceptable work for women since the first mechanized factories opened in the late 18th century....

And back into the early years of the European cotton printing industry.

These women are adding dye details with brushes, called penciling.

Applying pattern with a wood block

Nineteenth-century employee perhaps doing the metal work on a calico

printing cylinder.

We do not find so much about textile designers creating pattern for industry as we do pattern makers selling to craftswoman, but Wakefield's advice was reasonable and female designers do appear in records.

Mary Phinney Von Olnhausen (1818-1902)

You may remember her as a nurse in the television

series Mercy Street

Mary Phinney Von Olnhausen's Civil War memoir mentions her career as a textile designer. Single, left to her own devices in 1849 after her father died, the 31-year-old enrolled in Boston's School for Design for Women, one of several institutions founded in the 1840s and '50s to train women in occupational skills and to assist American manufacturers with product quality.

A Cocheco Mill print from an 1884 sample book

in the Cooper Hewitt

Mary Phinney went on to work as a textile designer at the Cocheco Mills in Dover, New Hampshire and the Manchester Mills in Manchester before volunteering to work in Union hospitals during the war. She married a German-born dyer she met in New Hampshire.

Philadelphia School of Design for Women.

Edwin Forrest House, which still stands

The Philadelphia school was founded as a private charity by Sarah Worthington Peters in 1848

Sarah Worthington King Peters (1800-1877)

The school was taken over as a branch of the Franklin Institute in 1850, becoming the largest art school for women in the U. S. under director Emily Sartrain at the end of the century.

Emily Sartrain (1841-1927) at 27

She was a professional mezzotint engraver.

Again, women learned commercial arts such as lithography, design for wallpaper, carpeting and other textiles and wood engraving, the method used for newspaper and magazine illustration.

How many of the design school graduates obtained jobs in textile design is unknown, but there must have been a reasonable chance of employment or the schools would not have been so successful. How many female "pattern drawers" made a living either in free-lance work or as mill employees is also unknown.

How many of the design school graduates obtained jobs in textile design is unknown, but there must have been a reasonable chance of employment or the schools would not have been so successful. How many female "pattern drawers" made a living either in free-lance work or as mill employees is also unknown.

Mallow wallpaper design by Englishwoman

Kate Faulkner for Morris & Company

Collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum