Lynn A. Bonfield in her 1988 Uncoverings study "Diaries of New England Quilters Before 1860" also found it difficult to determine if diarists were quilting for pay. One exception: In 1845 Persis Sibley Andrews had her hired girl Costella helping with quilting. "Costella quilts well and fast." But could you call Costella a professional quilter or was she just general household help?

A 1908 postcard from Mrs. A.P.N. of Kinglsey, Iowa to her niece:

Tell George his quilt is ready for him any time he comes down."

Front of the postcard

Is Mrs. N. making George a quilt as a gift or a financial transaction?

Note in a scrapbook picturing Esther Searl, Rosepine, Louisiana.

"At the age of eighty she did the fine quilting on all my quilts of which I am so proud."

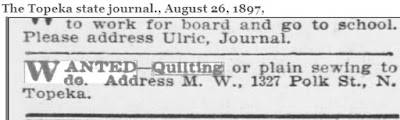

Advertisements

Advertisements are far less ambiguous. This 1897 newspaper ad

indicates M. W. wants "Quilting or plain sewing."

See a post about ads for quilt work here:

"Any one wanting quilting or sewing done see Mrs. Ryan."

Waxahachie Texas, 1910

Those ads go back to Colonial days:

"Quilting work of all kinds performed at the subscriber's house in Annapolis, in the best and newest Manner, as cheap as in London; by a Person from England brought up in the said Business."

Ad from Symon Duff, May 24, 1745, Maryland Gazette

Indexes to Occupations

I did a post about Colonial ads here:

My sources for much of the early information was from an index to occupations, MESDA's (Museum of Southern Decorative Arts) Craftsman Database, searching for words like quilting and quilter. Indexes like this one are a good source but digitization is not always available.

The occupation of quilter is better documented in the British Isles. I found this statement on line concerning quilting:

"The bed quilt made of patches was the staple product, but other articles such as tea cosies, cushion covers and warm clothing were also traditional. Usually handed down from mother to daughter rather than by an apprenticeship system [Is this true?], the craft has enjoyed a revival for the luxury market through the Women’s Institutes, especially in Durham. Arnold (The Shell Book of Country Crafts. John Baker,1968 and All Made by Hand. John Baker, London, 1970), and Wymer (English Country Crafts. A Survey of Their Development from Early Times to Present Day. Batsford, London, 1946) offer descriptions and a quilters index exists. [Where?]

Some indexes look very promising:

Dorothy Provine, an archivist in the Civil Archives Division of the National Archives in Washington, authored an article “The Economic Position of the Free Blacks in Washington, D.C., 1800-1860” and a District of Columbia Free Negroes Register, 1821-1861, which list occupations.

The R.G. Dun Credit Reports from the 19th century include much information about businesses gathered by local reporters to the agency.

https://www.library.hbs.edu/index.php/Services/Research-Services-for-the-R.G.-Dun-Co.-Collection

One enormous index to occupations is U.S. census records---occupations are listed from 1850 but sorting through those records is not easy and unfortunately not too informative so far:

Terry Terrell wrote me a note about a woman she found in the 1860 census with the occupation of quilter. The 1860 Census of Barnesville, Belmont County, Ohio lists Sarah Hanshaw (either 58 or 38 years old---hard to read) living alone with the profession of "quilter."

"Her 'value of estate owned'" was $50, and there was no 'value of real estate' listed. She was financially in the bottom third of the people in her immediate neighborhood."

Barnesville about 1910

"I haven't been able to find her in a later census....Barnesville at that time was a prosperous small town with a mainly farming economy. It had a B&O railroad station, and was just off the Cumberland trail, so not remote or difficult to access, but 25 mi. from Wheeling, WV to the east and Zanesville, OH to the west. Still, I found it odd that there was enough business to support a quilter. Though I know people made a living as quilters in Britain, I haven't seen it listed as an occupation anywhere else in the U.S. census after about 25 years doing genealogy as a hobby."

"In any case, it is interesting that at least one person appears to have been trying to make a living as a quilter in 1860 in a small town fairly far from a major urban area. Perhaps we need to unlearn the idea that 'checkbook quilting' is a new phenomenon."

Nellie's sisters-in-law were "quiltmakers, working out."

Sharon at PatchworkBitsAndPieces wrote a comment on this blog:

"I have census records for Joan and Barbara Sellar, sisters from Scotland. They immigrated with their family to USA in 1907. In 1910 the household of ten were living in Chicago. The men were plasterers, and both Joan and Barbara are listed as "quilt makers; working out". They are listed as wage earners with no weeks out of work. Perhaps they were making up blocks at home for a company like Ladies Art. Their future sister-in-law Nellie is one of the block makers in a friendship quilt in my collection."

As Terry notes, it's an occupation you don't often come across, but the censuses (censii?) offer an interesting data set.

Mrs. Clarence Pace, Louisiana, from the Library of Congress photographs

Photographs and Illustrations

Photographs after 1840 and illustrations back into the 18th-century show women at quilt frames, but again, interpretation is subjective. See a post on looking at the Farm Security photographs from the 1930s and '40s here:

Nottingham Lace-Running or Embroidering

Charles Knight, Pictorial Gallery of Arts, 1858

I found two photos of this woman showing off her quilt blocks.

What's going on?

Oral Histories: Interviews, family history and personal accounts

Oral histories may be the most useful source for information about 20th century professional quilters. We have a wealth of digital transcripts but searching and sorting are never easy. The Quilt Alliance's Save Our Stories has transcripts on line, but hard to search for words like "paid", "earned", etc. The state quilt projects, digitized in the Quilt Index also has interview snippets.

Emma Crockett of Alabama believed she

was about 79 or 80 years old when interviewed.

She worried about her memory in her interview.

Trying to find information about quilt work before 1900 is more difficult. One source is the W.P.A. Ex-Slave Narratives, which were collected in 1937 and 1938. The limitations on the accuracy of the data include the poor reflection of life in actual slavery collected from elderly people seventy years after emancipation. Some interviewees professed to be 130 years old, but the majority were probably young children during slavery like Emma Crockett who was younger than ten. The Narratives' value as documentation about quilts during slavery is low; but people did often talk about their lives after slavery.

Laura Ramsey Parker was interviewed in Nashville when she was 87. She recalled being taught to spin and weave while in slavery as a child. Soon after she was freed she went to Wisconsin but returned to Tennessee.

"Have worked all my life seems to me. At one time I was a chambermaid...later a sick nurse, a seamstress, dressmaker but now I piece and sell bed quilts."

Minerva Cline and quilts

These fragments of biography give us some clues. I find fragments to be widespread; comprehensive accounts to be few.

Another snippet or two:

On this blog Joanne left a comment:

"My grandmother was poor and quilted for herself and for others. Quilting was how she expressed herself and how she earned needed cash."

And Dianne's comment:

"I've always wondered about all the orphan blocks I inherited from my grandma. She was a single mother in the 30's and raised her 2 children by making quilts, baking, ironing and taking in boarders. I inherited ALL of her quilt patterns, quilting templates, bits and bobs of fabric etc. and was amazed at the amount of orphan blocks she had, there were also letters from her customers telling her to use what color for which piece and to add the cost of the fabric to their bill. She had several complicated blocks that had different color swatches pinned to different pieces so she could see what they would look like in the different color ways. I always thought I'd put them all together in a sampler but now I think I will leave them as they are."

Looking for a thesis project on quilting, women's history or economics?